In 2020, extreme weather events of unprecedented severity and scale have threatened human livelihoods especially in vulnerable communities (CRED & UNDRR, 2020). Such disastrous events are expected to become more frequent and intense, according to the 2021 IPCC report (IPCC, 2021). Adaptation of communities and states to a changing climate has been on top of the agenda at the recent 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

In this blog post, we wish to draw attention to the issue of legitimacy of global governance institutions such as the UNFCCC and its conferences. We will highlight a central finding in our research on global governance legitimacy, and discuss implications for a democratic and successful conversation about adaptation in global governance, including the COPs.

Legitimacy is a core issue in global governance. To the extent legitimacy prevails, a governing institution tends to have greater stability and problem-solving capacity. When people find a governing institution such as the UNFCCC legitimate, they generally are more eager to participate in its processes, to contribute resources, to embrace policies, which ultimately can provide governments with incentives to take more ambitious policy solutions at the global level. For example, strong public’s beliefs in the legitimacy of the UNFCCC can lead governments to pledge to provide more adaptation funding at COP meetings to lead by example.

To the extent that legitimacy is missing, global governance tends to face greater volatility and dysfunction, and may see greater emphasis on geopolitics and the prevalence of national interest politics in the future. Illegitimacy beliefs in global politics can also lead to further discourage state participation and restrict funding. Low legitimacy levels among citizens may also lead to a situation where greater publics are critical while elites are out of touch with the general population regarding the consequences of global governance. This might be the source of a weakened democratic discourse in which adaptation challenges such as justice and legitimacy are not properly discussed.

In a recent study, part of the GlocalClim research team examined, together with colleagues from the LegGov research program, elite and citizen legitimacy beliefs based on survey data on legitimacy beliefs among both different types of elites and citizens. These survey data collections were funded by the LegGov research program. Two parallel surveys were undertaken during 2017-2019, respectively of elite and public opinion, enabling a unique direct comparative analysis between elite and citizen opinion. The LegGov Elite Survey is unique in gathering detailed evidence from political and societal leaders in Brazil, Germany, Philippines, Russia, South Africa, and the United States. Regarding citizen opinion the LegGov team has developed the first battery of questions in the World Values Survey concerning the legitimacy of a range of global organizations.

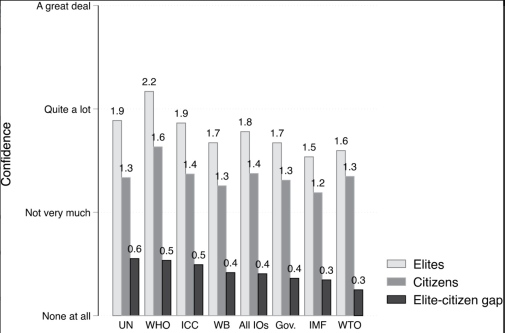

Based on these data, this study mapped the extent to which global governance institutions are perceived as legitimate. Figure 1 shows mean legitimacy levels for five countries (Brazil, Germany, Philippines, United Kingdom, and United States), disaggregated by organization. The figure compares elites with citizens in their respective countries, thereby illustrating the elite-citizen legitimacy gap. There are two main findings. First, citizens hold medium levels of trust in global governance institutions. Second, elites tend to have more confidence in global institutions compared with citizens at large, confirming the existence of a gap in legitimacy beliefs. This divergence between elite and citizen views holds for all six organizations.

What are the implications for global adaptation governance? Based on previous adaptation and legitimacy research (e.g., McGregor et al. 2020), here we put forward that it is essential to improve the legitimacy of both processes and outcomes in global adaptation governance by promoting just inclusion of citizens into global governance processes. The recently launched 2021 IPCC Report supports this idea, highlighting that the provision of local knowledge, for instance held by indigenous peoples, increases opportunities for successful policies and programmes and for enhanced legitimacy in the form of stakeholders’ trust (IPCC, 2021, p. 10-6). We also know from the legitimacy literature that people tend to care both about global procedures and performance, which are thus both pathways to greater social legitimacy in global adaptation governance. Moreover, recent research indicates that environmental justice is an important, yet understudied, potential source of legitimacy. That adaptation actions are underfunded and include affected groups, such as indigenous people, only insufficiently, not only presents a challenge for social legitimacy, but also for perceived justice in global adaptation governance (Ciplet et al., 2013).

To conclude, if global governance institutions dealing with adaptation seek to strengthen their legitimacy, such institutions need to increase citizens' participation in their processes for delivering fair procedures and outcomes. Efforts to promote fairer procedures yield the promise of strengthened public trust in that global governance institutions use their power appropriately and pursue more effective adaptation policies that need to help millions of people whose livelihoods are at risk.

References

Ciplet, D., Roberts, J. T., & Khan, M. (2013). The Politics of International Climate Adaptation Funding: Justice and Divisions in the Greenhouse. Global Environmental Politics, 13(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00153

Dellmuth, L., Scholte, J., Tallberg, J., & Verhaegen, S. (2021). The Elite–Citizen Gap in International Organization Legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 1-18. doi:10.1017/S0003055421000824

IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf (subject to revision)

McGregor, D. (2018). Indigenous Environmental Justice, Knowledge, and Law. Kalfou, 5(2), 279. ProQuest Central Student. https://doi.org/10.15367/kf.v5i2.213